An Olympic Hopeful

No, this pin doesn't come from an alternate universe. This pin was manufactured to promote Detroit's sixth bid for the Summer Olympics. Although Detroit was viewed by many as a sure bet for host city, the city lost out to Mexico City for the 1968 games.

No, this pin doesn't come from an alternate universe. This pin was manufactured to promote Detroit's sixth bid for the Summer Olympics. Although Detroit was viewed by many as a sure bet for host city, the city lost out to Mexico City for the 1968 games.

Think back to some of the iconic Olympic moments of the mid-twentieth century--Muhammad Ali’s 1960 gold medal, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised fists in 1968, and Mark Spitz’s 1972 world record--each of these could have happened in Detroit, had the city’s Olympic committees had their way. As long-time readers know, Detroit had long sought to host the international competition. In 1944, the city lost its bid to London, only for the games to be canceled while World War II raged. The city again bid for the 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968, and 1972 games, but fell short each time. The city's seven bids--more than any other city in the history of the games--is itself an Olympic record of sorts.

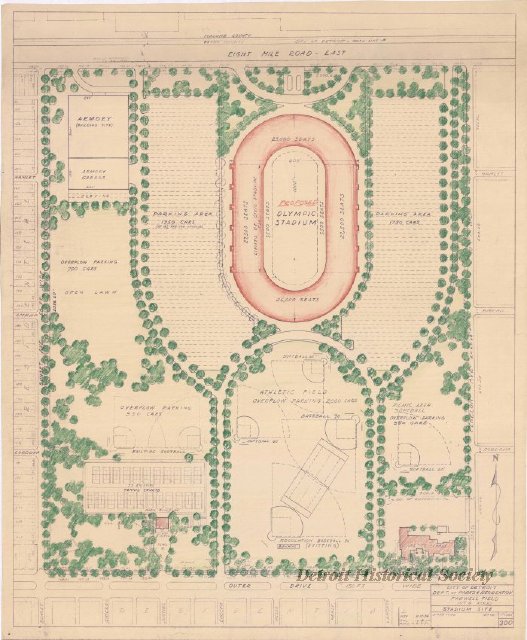

The city's pitch for the 1960 Olympics included this stadium in Farwell Field, beside the Michigan Light Guard Armory on 8 Mile Road.

The city's pitch for the 1960 Olympics included this stadium in Farwell Field, beside the Michigan Light Guard Armory on 8 Mile Road.

The city came closest in in the 1968 bid. With Detroiters Avery Brundage and Douglas Roby on the International Olympic Committee, the city appeared to have an advantage going into the 1963 summit in the West German city of Baden-Baden that would decide the host city. Detroit’s stiffest competition was thought to be from the relatively small city of Lyon, France, although Buenos Aires and Mexico City were also in the running. In addition to the games having never been held in a so-called “third world” country, Mexico City’s fatal flaw was thought it be its high altitude, which had caused problems for athletes when the city hosted the 1955 Pan-American Games.

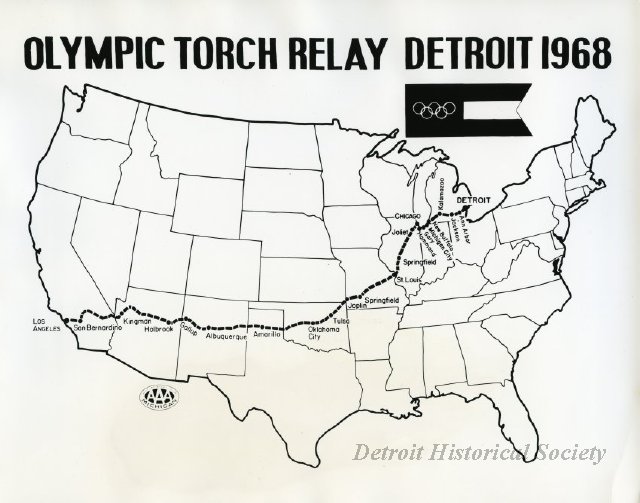

Detroit's Olympic Committee staged a cross-country torch relay as part of their campaign to secure the 1968 Olympics.

Detroit's Olympic Committee staged a cross-country torch relay as part of their campaign to secure the 1968 Olympics.

As a promotional event ahead of the meeting in West Germany, the Detroit Olympic committee sponsored a 2,521 mile long torch relay symbolically starting at the nation’s previous Olympic host city, Los Angeles, crossing Route 66, and I-94, and ending in front of the Spirit of Detroit statue. In a recorded address to the committee at Baden-Baden, President John F. Kennedy stated that “Detroit is the center of a great sports community in central United States,” and that here the games will receive the “warmest and most cordial welcome in the United States.” He closed his message by telling the International Olympic committee that he wished “the wisdom ascribed to the Olympian gods in arriving at your very difficult decision.” While we cannot say for sure of the role that the wisdom of Zeus and Athena played in the deliberations, it is generally maintained that Cold War politics hurt Detroit's odds. The participation of a separate East German team had been a point of contention between the International Olympic Committee and the nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. With both the United States and France poised to forbid the team from competing, Mexico emerged as a dark horse in the host city race, and ended up winning the bid with 30 votes to Detroit’s 14.

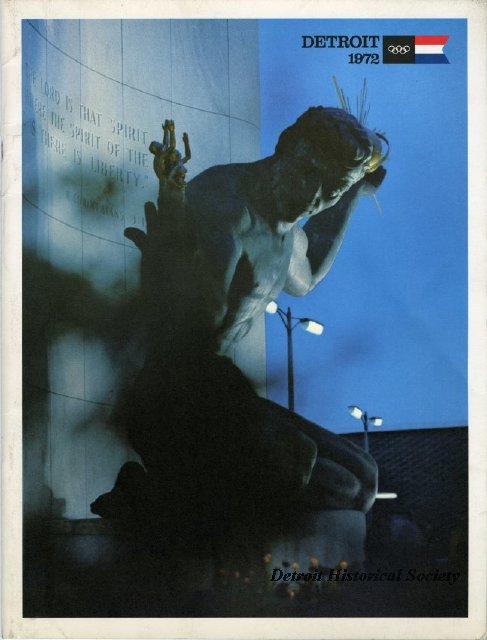

As part of the 1972 bid, the Detroit Olympic Committee published this large-format book. The first half of the book, "Detroit's Reply" contains information about the city's ability and suitability to host the games. In the second half, the proposed venues for the games are profiled. The book is also filled with artistic photographs casting the city in the best possible light. A nearly identical book was also produced as part of the bid for the 1968 games.

As part of the 1972 bid, the Detroit Olympic Committee published this large-format book. The first half of the book, "Detroit's Reply" contains information about the city's ability and suitability to host the games. In the second half, the proposed venues for the games are profiled. The book is also filled with artistic photographs casting the city in the best possible light. A nearly identical book was also produced as part of the bid for the 1968 games.

In the games, second place would have netted Detroit a silver medal, but in the arena of the International Olympic Committee, Detroit was merely left with the groundwork for another bid. In 1966, the city tried once more, reusing many of the elements from its previous plan. Local film studio, the Jam Handy Organization (appropriately enough named after the former Olympic swimmer who headed it) even produced the film, “Detroit: City on the Move” to try to entice the committee with a tour of the city’s modern amenities and facilities, narrated by Mayor Jerome P. Cavanagh. Despite these efforts, this time the city fell dead last behind Munich, Madrid, and Montreal. In 1970, Los Angeles replaced Detroit as the United States’ nominee, and in 1978 that city secured its place as the host of the 1984 Olympics.

The Detroit Historical Society is proud to present the first high definition version of "Detroit: City on the Move" available online. This video was sourced from a 16mm print in the Society's collection.

While the games never came to Detroit, numerous Detroiters certainly made it out to the games. Eddie Tolan earned the title of “world’s fastest human” in the 1932 Olympics, as we covered in this 2012 post. Throughout the 1970s Shelia Young competed in the summer games as a cyclist, and in the winter games as a speed skater. Most recently, Detroiter Katelin Snyder took home a gold medal in rowing from Rio de Janeiro. With recent talk of combating the rising costs of the games by holding them in a single location year after year, Detroit's Olympic dreams will likely go unfulfilled, however, its citizens will surely continue to take their places on the winners' podiums for years to come.

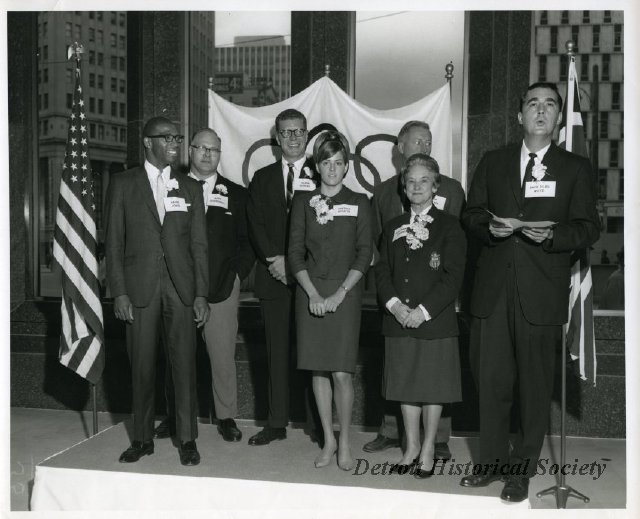

In this 1965 shot, WXYZ-TV's Dave Diles poses with a group of Detroit Olympians. The group includes swimmer Cynthia Goyette, hurdler Hayes Jones, swimmer Clarke Scholes, weight lifter Norbert Schemansky, and diver Betty Pinkston Campbell.

In this 1965 shot, WXYZ-TV's Dave Diles poses with a group of Detroit Olympians. The group includes swimmer Cynthia Goyette, hurdler Hayes Jones, swimmer Clarke Scholes, weight lifter Norbert Schemansky, and diver Betty Pinkston Campbell.