Top o’ the World, Ma!

Imagine that you are fourteen years old in 1911, and your dad is into the latest transportation fad—not automobiles, but aeroplanes! He and nine of his buddies are so smitten with the new technology that they contract with the Wright Brothers to have their newest biplane and best pilot come to Detroit for three days of “test driving.” Now imagine that you get to go for a ride with the finest aviator in North America, Frank Coffyn, who has over a year’s experience flying for the Wright team. After ten minutes in the air, you hold the record as the youngest person in the country to have flown on an airplane! That’s exactly what happened to Miss Josephine Alger.

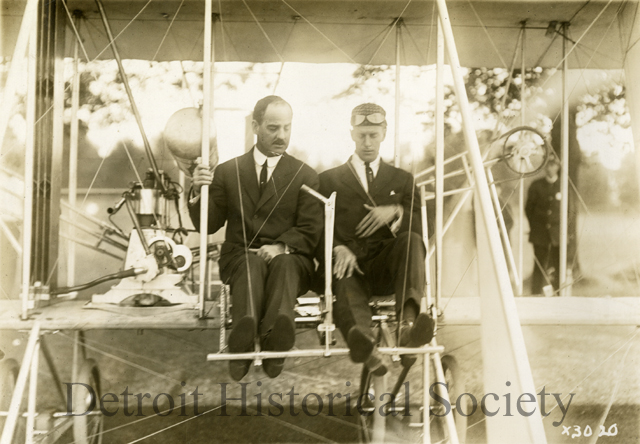

Imagine that you are fourteen years old in 1911, and your dad is into the latest transportation fad—not automobiles, but aeroplanes! He and nine of his buddies are so smitten with the new technology that they contract with the Wright Brothers to have their newest biplane and best pilot come to Detroit for three days of “test driving.” Now imagine that you get to go for a ride with the finest aviator in North America, Frank Coffyn, who has over a year’s experience flying for the Wright team. After ten minutes in the air, you hold the record as the youngest person in the country to have flown on an airplane! That’s exactly what happened to Miss Josephine Alger.  This story recently came to light at the Collections Resource Center when we “found” a scrapbook high on a shelf in the archives. An engraved cover bears the title “Aviation Meet of the Aero Club of Michigan at the Golf Links of the Country Club, Grosse Pointe Farms.” The book carries a warm, hand-written dedicatory inscription to Mrs. D. Dwight Douglas—Josephine’s married name—from Orville Wright, dated August 1945. The content includes the original invitation sent to club members, numerous newspaper clippings detailing the event, and twenty-five priceless photographs. As a time capsule, this book captures the very early days of Detroit’s love affair with airplanes—a rich history that most Detroiters don’t know. Just a year earlier, Archibald Hoxsey and Ralph Johnson had taken the first powered flights in the state at the Michigan State Fairgrounds (by the end of 1910, both pilots had perished in crashes). The men of the Aero Club—Fred and Russell Alger, William Metzger, Roy Chapin, Burns Henry, Alvin McCauley, and other industrialists—saw opportunity in aircraft as they had in automobiles. Thus the Aviation Meet was born.

This story recently came to light at the Collections Resource Center when we “found” a scrapbook high on a shelf in the archives. An engraved cover bears the title “Aviation Meet of the Aero Club of Michigan at the Golf Links of the Country Club, Grosse Pointe Farms.” The book carries a warm, hand-written dedicatory inscription to Mrs. D. Dwight Douglas—Josephine’s married name—from Orville Wright, dated August 1945. The content includes the original invitation sent to club members, numerous newspaper clippings detailing the event, and twenty-five priceless photographs. As a time capsule, this book captures the very early days of Detroit’s love affair with airplanes—a rich history that most Detroiters don’t know. Just a year earlier, Archibald Hoxsey and Ralph Johnson had taken the first powered flights in the state at the Michigan State Fairgrounds (by the end of 1910, both pilots had perished in crashes). The men of the Aero Club—Fred and Russell Alger, William Metzger, Roy Chapin, Burns Henry, Alvin McCauley, and other industrialists—saw opportunity in aircraft as they had in automobiles. Thus the Aviation Meet was born.  Over the course of three days, from June 19 to 21—Monday through Wednesday—forty-one members of the Aero Club and the Country Club [today the Country Club of Detroit] went for rides with “Birdman” Coffyn. Flights were scheduled in the early morning and late afternoon when the wind was lightest at the lakeside site.1 Generally, the plane motored up the coast for a mile or so, turned back over the Links for a couple of miles, and then around to the starting point. Curiously, while passengers wished to fly over Lake St. Clair, Coffyn demurred, perhaps thinking—in the worst case—that a crashed plane could be most easily salvaged on land. All of the flights went flawlessly. Frank Coffyn had a reputation for sober and calculated piloting; this was no barnstorming daredevil (surviving until 1960). He performed a few “trick” maneuvers for spectators while testing the plane alone, but airshow stunts were out of the question for his paying guests because there were no seatbelts. Much like early automobiles, it was considered safer to get thrown clear of wreckage in the event of a crash. Similar to the first Wright Flier, this craft was built of wood, fabric and cable, with some fancier touches like nickel plated pedal covers. The 4 cylinder engine produced 30 horsepower, propelling the plane at up to 60 miles per hour. Landings were often performed at a slow glide with the engine turned off. Passenger flights generally took about ten minutes, climbed to 400-500 feet and cost $25 [about $650 today].

Over the course of three days, from June 19 to 21—Monday through Wednesday—forty-one members of the Aero Club and the Country Club [today the Country Club of Detroit] went for rides with “Birdman” Coffyn. Flights were scheduled in the early morning and late afternoon when the wind was lightest at the lakeside site.1 Generally, the plane motored up the coast for a mile or so, turned back over the Links for a couple of miles, and then around to the starting point. Curiously, while passengers wished to fly over Lake St. Clair, Coffyn demurred, perhaps thinking—in the worst case—that a crashed plane could be most easily salvaged on land. All of the flights went flawlessly. Frank Coffyn had a reputation for sober and calculated piloting; this was no barnstorming daredevil (surviving until 1960). He performed a few “trick” maneuvers for spectators while testing the plane alone, but airshow stunts were out of the question for his paying guests because there were no seatbelts. Much like early automobiles, it was considered safer to get thrown clear of wreckage in the event of a crash. Similar to the first Wright Flier, this craft was built of wood, fabric and cable, with some fancier touches like nickel plated pedal covers. The 4 cylinder engine produced 30 horsepower, propelling the plane at up to 60 miles per hour. Landings were often performed at a slow glide with the engine turned off. Passenger flights generally took about ten minutes, climbed to 400-500 feet and cost $25 [about $650 today].  By the end of the Meet, several new records had been set and a few bets won. While there had been previous meets for spectators, this event was the first time that a private organization had sponsored such ride-alongs. On Monday morning, Coffyn took nine flights in 110 minutes; the previous record was eight in a full day. Wednesday, he took thirteen flights in two hours. Two of his passengers— Marion Alger (Russell’s wife) and Mary Alger (Fred’s wife)—became the first American women to fly on US soil.2 In all, ten of the 41 passengers were women. Unfortunately for Josephine Alger who flew on Monday, Wednesday morning’s schedule included twelve-year-old Horace Wadsworth, who snatched her record as the youngest aviator after just two days. Following the flights each passenger was interviewed by the newspapers, and two thoughts were enthusiastically repeated: the ride was very comfortable and exciting; and they were never scared. Never.

By the end of the Meet, several new records had been set and a few bets won. While there had been previous meets for spectators, this event was the first time that a private organization had sponsored such ride-alongs. On Monday morning, Coffyn took nine flights in 110 minutes; the previous record was eight in a full day. Wednesday, he took thirteen flights in two hours. Two of his passengers— Marion Alger (Russell’s wife) and Mary Alger (Fred’s wife)—became the first American women to fly on US soil.2 In all, ten of the 41 passengers were women. Unfortunately for Josephine Alger who flew on Monday, Wednesday morning’s schedule included twelve-year-old Horace Wadsworth, who snatched her record as the youngest aviator after just two days. Following the flights each passenger was interviewed by the newspapers, and two thoughts were enthusiastically repeated: the ride was very comfortable and exciting; and they were never scared. Never.  It should be noted that press access was limited. The public was afforded pretty good viewing along Fisher Road, adjacent to club grounds, and each morning a couple of hundred onlookers gathered to watch. Entrepreneurial youth began selling breakfast foods and snacks from impromptu stands and fared well over the three-day event. At least two reporters commented on local interest in the flights. On Monday morning, life in Grosse Pointe came to a halt while the plane was aloft, with everyone scanning the sky, following the sound of the engine. Two days later, residents no longer even looked up. By Wednesday the syndicate that brought the plane to Detroit had purchased it in order to further promote local aviation. They announced a open-to-the-public meet at the Fair Grounds to take place June 29 to July 4. Frank Coffyn taught Fred and Russell Alger to fly, and the three of them converted their biplane into a “Hydro-Aeroplane,” with pontoons to facilitate a water landing.3 From this point on, Detroit manufacturers—in fact, companies around Michigan—began hopping into the airplane business. Ford had tried in 1910, without success, but later became a leader in aviation under the direction of Bill Stout and his Stout Metal Airplane Company. Ford eventually bought Stout’s firm, and with the proceeds Stout started the first regularly scheduled, field-based passenger airline out of Ford Field in Dearborn. During the 1920s the Aircraft Development Corporation tried to become the General Motors of the skies, owning Ryan Aircraft, Lockheed Aircraft, and ten other firms. This company built the world’s only metal-skinned dirigible at Grosse Ile. In 1929, prior to the Great Depression, nineteen Detroit companies were building airplanes and airships, including such notable names as Stinson and Verville. Except for military construction during World War II, Detroit’s foray into aircraft manufacturing waned after the 1920s. During those first two decades, however, the city’s movers-and-shakers saw the opportunity in air travel. They were among the world’s first adopters, and we’ve got the book to prove it. For those interested in Michigan aviation history, there are many books available. Perhaps the best place to gain perspective is “A Chronology of Michigan Aviation: 1834-1953,” which lists notable events, people and products by date. This booklet was written by Robert S. Ball of the Detroit News, and published by the Michigan Department of Aeronautics in 1953.

It should be noted that press access was limited. The public was afforded pretty good viewing along Fisher Road, adjacent to club grounds, and each morning a couple of hundred onlookers gathered to watch. Entrepreneurial youth began selling breakfast foods and snacks from impromptu stands and fared well over the three-day event. At least two reporters commented on local interest in the flights. On Monday morning, life in Grosse Pointe came to a halt while the plane was aloft, with everyone scanning the sky, following the sound of the engine. Two days later, residents no longer even looked up. By Wednesday the syndicate that brought the plane to Detroit had purchased it in order to further promote local aviation. They announced a open-to-the-public meet at the Fair Grounds to take place June 29 to July 4. Frank Coffyn taught Fred and Russell Alger to fly, and the three of them converted their biplane into a “Hydro-Aeroplane,” with pontoons to facilitate a water landing.3 From this point on, Detroit manufacturers—in fact, companies around Michigan—began hopping into the airplane business. Ford had tried in 1910, without success, but later became a leader in aviation under the direction of Bill Stout and his Stout Metal Airplane Company. Ford eventually bought Stout’s firm, and with the proceeds Stout started the first regularly scheduled, field-based passenger airline out of Ford Field in Dearborn. During the 1920s the Aircraft Development Corporation tried to become the General Motors of the skies, owning Ryan Aircraft, Lockheed Aircraft, and ten other firms. This company built the world’s only metal-skinned dirigible at Grosse Ile. In 1929, prior to the Great Depression, nineteen Detroit companies were building airplanes and airships, including such notable names as Stinson and Verville. Except for military construction during World War II, Detroit’s foray into aircraft manufacturing waned after the 1920s. During those first two decades, however, the city’s movers-and-shakers saw the opportunity in air travel. They were among the world’s first adopters, and we’ve got the book to prove it. For those interested in Michigan aviation history, there are many books available. Perhaps the best place to gain perspective is “A Chronology of Michigan Aviation: 1834-1953,” which lists notable events, people and products by date. This booklet was written by Robert S. Ball of the Detroit News, and published by the Michigan Department of Aeronautics in 1953.

Footnotes

1. At this point the Country Club’s clubhouse occupied property on the southeast corner of Jefferson and Fisher roads—property later the site of Dodge’s Rose Terrace. As outlined in Tonnancour (Vol.2), the golf course occupied space the other side of Fisher, along current Beverly and McKinley avenues and over property now occupied by Grosse Pointe South High School. The present course north of Moross Avenue was opened in 1912. 2. While the publicity in 1911 touted the Grosse Pointe women as the first American ladies to fly, Wilbur Wright had taken American Edith Berg, wife of his European agent, for a ride over France in 1908. 3. “Coffin’s Hydro-Aeroplane” [sic] photos are part of the George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress.