Pandemic: Detroit’s Deadly History

The latest virulent health threat affecting our world seems new to most of us. The Ebola, SARS and MERS outbreaks were recent, but distant. Flu scares never cut this deep. So, in our collective memory, the mass closure of all public spaces is unique. “Novel” you might say. Among Detroit’s many, many stories there are tragic tales of devastating epidemics, mass self-isolation, unintended misinformation, poor preparedness and fantastic fatality rates. Times when, in the words of historian Silas Farmer, “business was entirely forgotten.” We are not doing this for the first time, just on a grander scale.1 The most recent of these was the 1918 flu epidemic when over 1,600 Detroiters died of either influenza or pneumonia through October and November – the equivalent of 2,258 people based on the city’s current population. More died the following Spring, and then the year after that. Yet even this is beyond our collective consciousness, so instead let us leap back another century.

Detroit as depicted on an 1837 banknote.

Detroit as depicted on an 1837 banknote.

In 1813, Americans in the Old Northwest were struggling to defeat of the colossal British Empire in the War of 1812. Soldiers and sailors from New York to Michigan were struck by a raging “pneumonia of a sthenic type,” today thought to be smallpox.2 Half of the sailors in both navies, prior to the Battle of Lake Erie, were bed ridden. At Detroit, half of the 2,527-man garrison was incapacitated, and hundreds of soldiers and citizens died. Afterward, vaccination became socially mandatory. A greater threat arose, not completely without warning, in 1832. A strain of cholera had arrived in North America at Montreal from Europe via Russia and India, and was spreading along the East Coast. Anticipating an outbreak, the Detroit City Council closed the Canadian border in June and opened a containment “hospital.” Strangers were not welcome. Ships were not allowed to dock, and passengers who debarked were quarantined. Then came the Black Hawk War. United States Army regulars were shipped by train and steamboat toward a tiny Chicago harbor, heading for the Mississippi River. In June, General Winfield Scott embarked almost a thousand generally healthy troops at Buffalo. They boarded four first-rate steamboats: Henry Clay, William Penn, Sheldon Thompson, and Superior. The Henry Clay and Sheldon Thompson were the first to leave Buffalo with troops. The Clay arrived at Detroit and within a day two soldiers succumbed to cholera. A general panic arose. The ship was made to leave the dock and anchor upstream of the town near Belle Isle. There was a belief that the disease was passed through the air as a vapor, and Belle Isle was downwind of Detroit. Unfortunately, the cholera pathogen is waterborne, making upstream Belle Isle the worst location for the vessel to anchor. Cholera bacteria does not spread directly person-to-person – different than the current situation – but is transmitted through contaminated water sources or food. Infection results in rapid and fatal dehydration, and critically, there is a lag time between exposure and evincing symptoms.3 Detroit fared badly. Fear spread quickly after two citizens were sickened on July 6, two days after the Henry Clay arrived. Many people tried to escape the village, but found hotels and taverns unwelcoming. Pontiac residents, twenty miles north of the city, turned outsiders away with guns, and Rochester citizens tore up their bridge. Mail stopped being distributed. New immigrants were told to leave town. Despite a spate of homeopathic remedies and prayer, ninety-six people died, or about 4.3 percent of the population. This included Fr. Gabriel Richard, the Roman Catholic pastor and a leading political citizen, who had been tending the sick.4

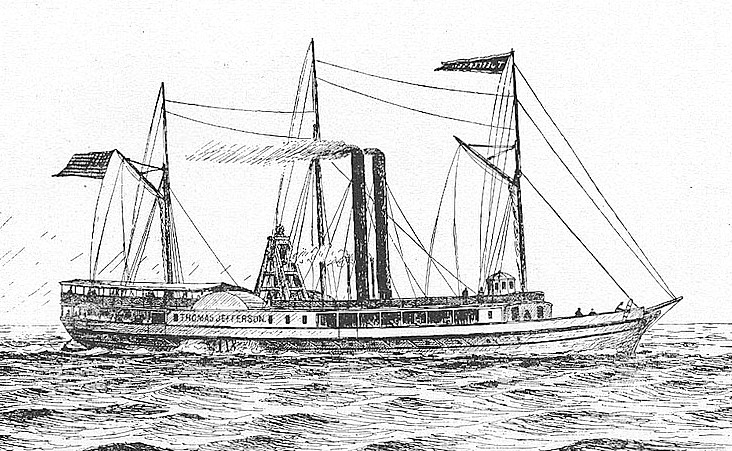

While we have no images of the steamboats that visited Detroit in 1834, the Thomas Jefferson is similar in size and accommodation.

While we have no images of the steamboats that visited Detroit in 1834, the Thomas Jefferson is similar in size and accommodation.

The “visitation” was repeated in 1834, running from the beginning of August through the end of September. While the flow of immigration didn’t stop, people arriving were inspected and encouraged to move on. At the height of the contagion, seven percent of population died in a four-week period – roughly 350 people and as many as 16 per day. Half of them were new to town. Mayor Charles Trowbridge was a regular visitor to the town’s only hospital, where patients were cared for by a volunteer nursing corps that included Zach Chandler and John Farmer (Silas’s father). Fr. Martin Kundig, Richard’s replacement, bought a small abandoned protestant church and repurposed it into a hospital, assisted in his efforts by the Sister of Ste. Claire. “Pesthouses” were established in the countryside where the afflicted were consigned. On June 26, the Detroit Courier touted the benefits of hygiene to fight the scourge. “We have less faith in quarantine and non-intercourse than in a thorough system of cleanliness, both indoors and out.” In other words, wash your hands.5 Traditionally, when a Detroiter died the bell on Ste. Anne’s Church was rung. Because of the depressing frequency, this practice was suspended. Funeral services were abbreviated, and public gathering suspended. As taverns and hotels were also home to citizens and refuges for travelers, they did not close. In fact, alcohol was considered the only safe thing to drink. Cholera returned to the city in 1849. In July, 781 people were buried, or about four percent of residents. Two months of the pestilence returned in the summer of 1854, killing roughly 260 in July – now less than one percent of residents in this rapidly growing city. With improvements to local drainage, sewage management and the water system, as well as improved hygiene protocol and training, Detroit’s history with cholera eventually waned. Even so, health care professionals dealt with seasonal outbreaks of diseases like flu, pleurisy, ague, typhoid, and dysentery. Some, like flu, remain problems today. The disappearing-toilet-paper affliction is relatively new, and recently reached historic proportions. To add perspective, the seven percent mortality rate experienced in 1834 would translate to over 47,000 of the city’s current population. Sometimes there is solace, however minor, in history.

[1] Farmer, Silas. “History of Detroit and Michigan.” (Detroit: Silas Farmer Co., 1884; accessed March 2020 at https://books.google.com/books?id=RH9FDeAyUJ4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=silas+farmer+history+of+Detroit&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj7sKOm7KHoAhXCAp0JHfGHBDoQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=silas%20farmer%20history%20of%20Detroit&f=false) 49; Walker, Captain Augustus. “Early Days On The Lakes, With An Account Of The Cholera Visitation Of 1832.” (From Manuscript Records of the Buffalo Historical Society, accessed in March 2020 at: http://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/Documents/walker/default.asp?ID=c1) [2] Anderson, Fannie. “Doctors Under Three Flags,” (WSU Press, 1951) 118. [3] Gillett, Mary C. “Army Medical Department, 1818-1865.” (Washington, D.C.; U.S. Government Printing Office), p50-51, accessed in May 2014 at http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/civil/gillett2/amedd_1818-1865_chpt2.html; Michigan History magazine cited at http://clarke.cmich.edu/resource_tab/information_and_exhibits/michigan_historical_calendar/07_july/july_4.html in Jan2013 [4]Farmer, 48-50; Hill, Henry Wayland, ed. Municipality of Buffalo, New York, A History. 1720-1923. (Lewis Historical Publishing Company: New York, 1923), accessed in May 2014 at http://www.buffalonian.com/history/articles/1801-50/cholera32.html [5] Detroit Courier, June 26, 1834